- A unique place

- Habitats, Flora and Fauna

- Evolution of the Heath’s two topographies

- Human activity on the Heath

A unique place

Headley Heath is a unique botanical site. It has a very rare range of flora due to alkaline and acidic soils being found next to each other.

The juxtaposition of such different soils comes from the evolution of its landform over millions of years which has resulted in the Heath having two distinct topographies – a flat plateau and deep incised dry valleys.

The Heath has been influenced also by human activity since the Mesolithic Age (15000-5000 BC) which has radically changed the Heath’s natural vegetation.

Because it is such an important place, the Heath is protected by 3 planning designations:-

- It is within the Surrey Hills National Landscape. This designation aims to conserve and enhance areas of outstanding beauty.

- It is within the Metropolitan Green Belt. In the Heath’s case, this designation is primarily to protect it from encroachment by development.

It is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. This designation reflects its rich, varied, and sometimes rare, flora and fauna made up of a wonderful mosaic of open heath, chalk downland slopes and mixed woodland.

Habitats, Flora and Fauna

The Heath has 4 habitats: heathland, chalk downland, woodland and ponds.

Heathland

The heathland has acid soils comprised of sands and shingle. The main plants which thrive in this environment are Bell Heather and Dwarf Gorse.

Chalk Downland

The chalk downland has alkaline, fast-draining soils with low nutrients and high levels of calcium carbonate. No plant species can dominate resulting in a very rich habitat with great diversity of plants and animals.

Among the mixed vegetation are many wildflowers including wild thyme, dropwort, bird’s-foot-trefoil, salad burnet, common knapweed, marjoram and kidney vetch

.

Woodland

The Heath’s woodland is found mainly in the south and west of the Heath. Here the soil is clay with flints supporting beech, silver birch, goat willow, oak and rowan.

Ponds

Grasses and rushes thrive near the water’s edge and in some ponds, the very rare Starfruit plant is found. Dragonfly nymphs, smooth, palmate and great-crested newts, toads, frogs, ducks and mandarin ducks, moorhens and herons.

Evolution of the Heath’s two topographies

The two topographies are the result of (a) the evolution of the landform in the south-east by geological, tectonic and geomorphological processes acting over millions of years and (b) river erosion creating valleys on the Heath during the last Ice Age (115,000-11,700 years ago).

Geological, tectonic and geomorphological processes

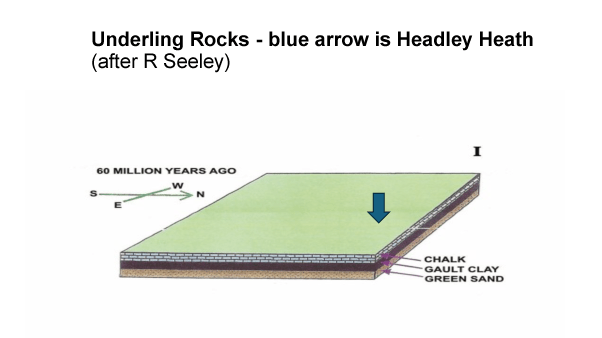

The first stage in (a) was the depositing of the underlying rocks. Beginning with the Greensand some 100-90 million years ago, it finished with the deposition of the chalk 60 million years ago. The chalk was laid down in a shallow sea in the tropics after which continental drift moved it to its present position some 50 degrees north.

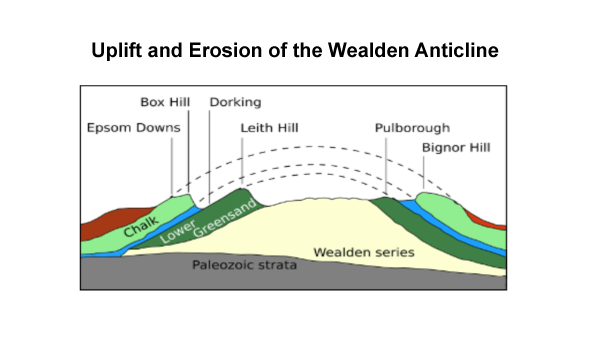

The second stage was a long period of successive uplifts, erosion and changes in sea level. One of these uplifts some 20 million years ago folded the underlying rocks to form the Wealden Anticline the higher parts of which may have exceeded 3000 feet.

The fold was created by the African tectonic plate colliding with the Eurasian tectonic plate and pushing the latter upwards making the Wealden Anticline an outer ripple of the creation of the Alps.

A long period of erosion then reduced the anticline to a plain leaving the North and South Downs and the High Weald as peaks rising above the plain. The plain was just above sea level.

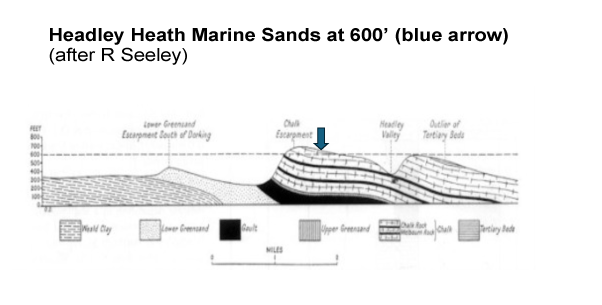

The next significant event was rising sea level 3 million years ago which flooded the plain leaving the Weald as an island and the North Downs as 650 feet peaks.

The sea deposited new marine sands on the lower parts of the plain. When sea level fell 2.6 million years ago, it exposed the new sands and a new cycle of erosion began which removed much of them.

However, some sands were left in a few locations at the 600 feet contour, one of which now forms the sandy plateau of Headley Heath.

Creation of the dry valleys

The creation of the Heath’s second topography, the dry valleys, happened comparatively recently during the last Ice Age. About 450,000 years ago, the ice sheets reached as far south as Finchley in North London.

The land south of London, though free of ice, was still tundra with frozen l some several metres deep. In summer the surface of the tundra melted releasing water which flowed downhill across the chalk creating shallow valleys.

With the advent of the present warm interglacial period, the tundra melted and surface water was able to sink through the pervious chalk leaving the valleys dry.

Human activity on the Heath

The unique nature of the |Heath’s flora is largely due to the very rare juxtaposition of the two different soils in the dry valleys and the plateau. The vegetation, however, has been shaped by human activity.

The natural vegetation for southern England is temperate woodland and the Heath was originally completely covered with trees. But humans cleared some of the woodland to create pasture for grazing animals

Stone Age Man to the Romans

Human activity dates from the Middle Stone Age (15,000-5000 BC). Stone Age man only passed through the area using its high ground to make nomadic travel easier.

Settlements were established nearby in the Iron Age (800 BC-43AD) when iron tools were available to partly clear the Heath for animal grazing.

The Romans settled the area attracted by the important road, Stane Street (from London Bridge to Chichester), which passed close by the Heath.

In 2013-2014 a field walking by the Plateau Archaeology Group found 1st century pottery Romano-British and imported Roman fine ware following ground disturbance by NT contractors removing birch scrub.

Anglo-Saxons to 1900

Little is known of the Heath area during the early Saxon times, but probably it continued much as in the Iron Age being used for grazing

By the Norman Conquest in 1066, the Heath was in the Manor of Headley held by Countess Goda, mother of King Harold of arrow fame.

Headley village is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. Then it was called ‘Hallega’ which means a clearing in the heather. The Heath was probably still used for grazing, but also the collection of furze, bracken and firewood by villagers.

The present heathland was largely created during the 17th and 18th centuries when Enclosure Acts redistributed the common land to landowners.

Tenants were granted Rights of Common to graze and collect wood. Most rights taken away in 1965, but one cottage still can graze geese on Headley Heath.

Modern Times

By 1900, the Heath existed much as today. The railways had arrived and the Heath was surrounded by the growing towns of Leatherhead, Epsom and Dorking.

In the second world war, it was requisitioned for training Canadian Corps of Engineers using earth moving equipment notably for the D-Day landings. Other uses included beacons to help aircraft navigate and some think an airstrip was built for the Special Operation Executive (SOE). On the same day in 1941, two RAF bombers damaged over Europe crashed onto the Heath.

In 1946, the Heath was given to the National Trust by the Crookenden family along with the Lordship of the Manor. In 1956, fires burnt half the heathland and new firebreaks and trails/walks were built around this time. In the 1970s the Aspen, Brown and Bellamoss ponds were created.

In 1967, the Government planned to route the new M25 through the Heath, but local opposition led to it being moved north where it opened in 1985.

With agricultural decline, grazing stopped and woodland began to re-establish itself. As a result, one of the National Trust’s main aims now is to stop this and maintain the open heathland and its accompanying plants and species. To help with this it has re-introduced grazing with a 9 strong herd of Belted Galloways.

The National Trust is helped in maintaining the Heath by volunteers undertaking work including: repairing fences; installing gates; scrub management; grassland management; taking care of livestock; tree maintenance; and helping visitors.

Today, the Heath hosts many different leisure activities including dog walking, horse riding, cycling, picnics, bird watching and hiking.

The National Trust and FOHH organise walks and talks and Headley & Old Freemans Cricket Club plays opposite the main car park in the summer.

Link to the National Trust Lizard Trail walk

Link to the National Trust Military Trail walk

A digitally remastered film of the Heath from 1964 by Humphrey Mackworth Praed can be viewed here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.